Developing a Learning Design System

Abstract

Over several years, the University of Adelaide has been working to develop its capability and capacity to develop fully online courses. The focus of this has been the development of a Learning Design System that provides a structured process, methodology, vocabulary and aesthetic to enable collaborative course development at scale. This system brings together diverse groups of people to collaborate and form deeper partnerships while developing engaging digital pedagogy for online courses. This paper will outline the various aspects of this system and how they relate to each other and support a quality learning experience.

Keywords: learning design, design process, design system,

Introduction

The Online Programs Team (OPT) at the University of Adelaide began life as the development team for AdelaideX, the institution's partnership with the MOOC platform EdX. The team led the University's exploration and innovation in online education (McDevitt, 2016), developing a suite of MOOC products. In 2019, the University partnered with an Online Program Management (OPM) provider to scale up the development of fully online postgraduate degree programs. This arrangement aimed to get products into the market while developing the OPT's capacity and capability to bring this work in-house.

Throughout 2019 and 2022 the OPT worked closely with the OPM to develop courses and programs. During this time the team also developed and launched six new MOOCs, and in 2021 the team was engaged to develop the research capstone courses across four online postgraduate programs, and then develop two fully online undergraduate programs for Open Universities Australia. Over the past four years, the team has expanded to deliver these new initiatives and maintain this expanded portfolio.

Framing a Systems Approach

Initially, the work undertaken by the OPT with the OPM was ad-hoc and responsive; as issues arose, they would be resolved to ensure the work continued. Those that would repeat became an area of concern, requiring more work, and a change would be suggested and documented. Through this iterative approach, the relationships between individuals, concepts, processes, events, actions and characteristics of a learning design system started to emerge. The team has had to respond to dealing with scale and working with large numbers of collaborators and stakeholders.

The arrangement with the OPM immediately required a deep engagement with the provider and the creation of shared standards and practices in the design and development of courses. This required work on a variety of scales. From program design and objectives to course structure and formatting. From small aesthetic decisions to the formalisation of course style guidelines. From specifying the student experience to developing details guides and assessment tools. This work was not the beginning of a singular artefact, approach or process - but an entire design system to ensure quality learning experiences were being delivered for every course. A system that could combine the technical, pedagogical and knowledge requirements with those of the organisation and work for the key contributors and stakeholders.

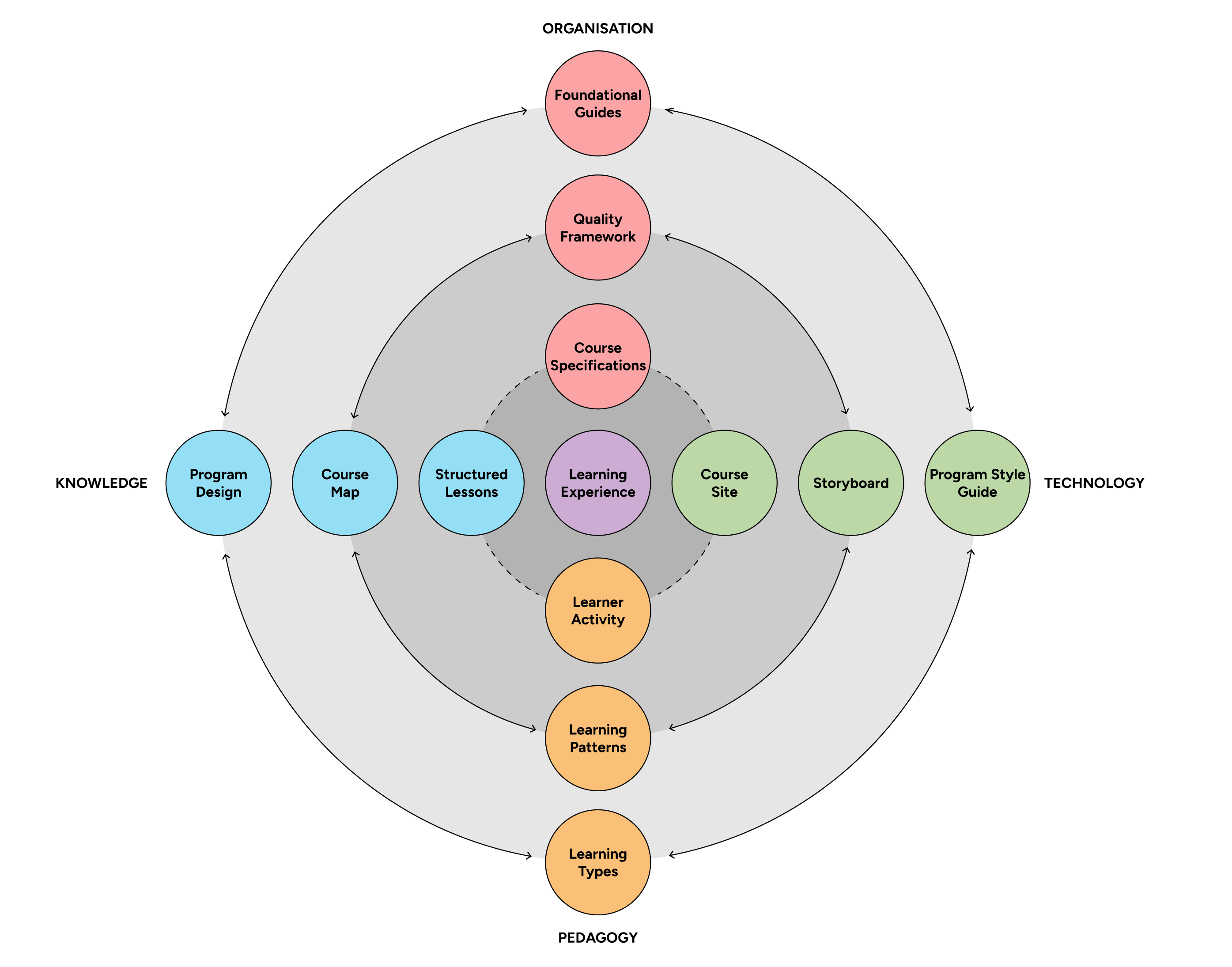

Figure 1: The facets and levels of a learning design system.

Endeavouring to create a system from nothing is not possible, so the development was incremental and organic. As issues arose, they would be addressed. Small pieces of a more extensive system emerged as needs arose, and we began formalising them through documentation. The team were also aware of the complexity of our role and situation. We were not working on a single project, discipline area, individual or platform – we worked across all these. What was also present, and part of our work, was seeing how the traditional one-size-fits-all approach was failing. Linear processes failed to cope with the complexities that large numbers of contributors caused. Often, dependencies would collide and back up, creating a scene similar to a car crash pileup. At our operational level, across the whole process, we could see that these were systemic issues, not isolated or caused by a single problem or point of failure. They were caused by the various individuals involved in developing a course, each with their own process, preferences, perspective and priorities intersecting with predetermined timelines and unmovable workflows.

We could see that adaptability needed to be built into the larger system, not to be Agile but agile and able to move according to the situation. While we couldn't change how the OPM worked, there were areas we could focus on and adapt our ways of working. Initially, we focused on the areas under our influence and control - ensuring clarity around the Organisation area. As more courses were handed to the team, we could focus on connecting the Pedagogy and Knowledge areas. As these became more formalised, developing specific processes and software to enhance the Technology area became possible.

This work aims to develop a systemic view of learning design, not just a singular approach, but to begin a process towards a more ontological view of learning design. Not the ontology but an ontology as a way of describing, according to Fensel (2001), “a shared and common understanding of a domain that can be communicated between people and application systems”.

The Learning Experience

Central to the whole system was defining the intended learning experience for the university’s online programs, one that was truly learner centred. Drawing on strategic documents, marketing material, student data, feedback and the experience from working on 25 MOOCs; the team assembled a language that helped to define five key aspects of the learning experience we wanted to create: Clear, Contextual, Interactive, Challenging and Personalised. Using each of these we developed clear expectations that the learner should have for their experience (Table 1) and the Adelaide Online Learning Experience was born. Laying down this foundational piece early on allowed us to develop the other aspects of the system.

Organisational Aspects

The first step in the OPM relationship was to establish clear roles and responsibilities. While much of the development work would be undertaken by the OPM, the academic roles were from the university, and Quality Assurance and relationship management sat with the OPT.

Quality Assurance seems like it would have a quick solution - there are a variety of systems and tools available, including Quality Matters (2023), TELAS (2020), and the Higher Education Standards Framework (2015). A drawback of these models is that they are structured as checklists - items being present in a course as quasi-measurements of quality. They act as an ingredient list rather than provide quantifiable aspects of quality. A wine label may tell you what is inside the bottle, but what tells you the wine is good? The first few courses that were developed ticked all of the boxes, yet many issues came up during the final reviews that required fixes before courses went live. These tended to focus on a less tangible metric – the learning experience. Yes, instructions are present on how to complete the assessment, but are not clear. Yes, information provided to the learner, but it is not contextualised and makes no sense.

These aspects came to define the Adelaide Online Learning Experience that was central to forming a broader Quality Framework that both organisations agreed to establish straightforward ways of working and drive the development of courses. Based on the defined learning experience, the framework was expanded to include clear measures that can be tied back to existing frameworks and that alignment can be seen in Table 1.1. This framework aimed to ensure the focus was required for the learning experience to be achieved rather than a specific technology or technical standards that change over time.

Table 1: Mapping of alignment of the Adelaide Online Learning Experience with existing quality frameworks TELAS (2020), Quality Matters (2023) and HESF (2015).

| Domain | Learner Expectation | TELAS Alignment | QM Alignment | HESF Alignment |

| Clear | - accessible and inclusive to all students - easy to understand and navigate (with sufficient instruction) - has defined goals and expectations - utilises technology that doesn’t get in the way of learning - explains the requirements for interactions - tests learning with appropriately timed, varied and suitable assessments - delivers content that is contemporary and relevant |

1.1, 1.2, 1.3, 2.1, 2.2, 3.1, 3.2, 3.3, 5.1 | 1.1, 1.2, 1.3, 1.4, 1.5, 1.7, 2.1, 2.3, 3.2, 4.2, 5.3, 5.4, 7.1, 7.2, 7.3, 7.4, 8.1, 8.2, 8.3. 8.4, 8.5, 8.6 | 1.4.1, 1.4.2, 1.4.3, 1.4.4, 1.4.5, 2.2.1, 2.3.3, 3.3.1, 3.3.2, 3.3.3, 3.3.4 |

| Contextual | - articulates each activity with purpose and intention - contextualises learning in the real world |

5.2, 5.3, 6.1, 7.1, 7.2, 8.1, 8.2 | 2.2, 2.4, 3.4, 4.4, 4.5 | 1.4.2, 1.4.4, 1.4.5, 3.1.2, 3.1.3, 3.2.1, 3.3.1 |

| Interactive | - learning is actively constructed, students learn by doing, not consuming - provides feedback that can be implemented to improve learning - promotes flexible communication between tutor and student - has a vibrant exchange of ideas, opinions, perspectives, and experiences |

1.4, 4.1, 4.3, 5.4, 5.5, 7.3 | 1.9, 3.3, 3.5, 4.1, 5.2, 6.2, 6.3 | 1.3.3, 1.4.2. 2.1.3, 3.2.1 |

| Challenging | - promotes further learning and provides those opportunities - creates new knowledge, skills and extends existing ones - has support from a teacher that is present throughout the course |

6.2, 4,2 | 1.8, 3.1, 4.3, 5.1, 6.1 | 1.4.3, 1.4.4, 1.4.5. 3.1.3. 3.2.2, 3.2.5 |

| Personalised | - adds value to the student and is purposeful - respects student time and commitment to study - develops skills that are relevant to their professional practice |

3.4, 3.5 | 1.6, 2.5, 6.4 | 1.3.3, 1.4.5. 2.1.3. 2.2.1, 2.3.2. 3.1.1. 3.1.2 |

Core aspects and components of the course were defined using the aims and intentions of the learning experience to create Foundational Guides to aid course development. These guides were developed to aid the different components of the course - assessments, discussions, rubrics, activities and blended institutional policies with good practice and examples. The learning experience also allowed us to develop a measurement tool, the Course Assessment Tool, to score courses and ensure that they passed a minimum standard and compare courses across the broader portfolio. Each of these elements combined to provide clear Course Specifications that aided future development by setting more explicit expectations for stakeholders and collaborators.

Pedagogy Aspects

So much of the role of a learning designer is facilitated through conversation and language. Therefore, language must be used to create a shared understanding between participants — between the designer, author, developer and student. Creating a common vocabulary becomes incredibly important when entering discussions where perspectives and experiences are radically different. The aim is to ensure that discussions are focussed on learning and ensure it is understood that learning can happen in a variety of ways. Stepping away from tools, technology and techniques to discuss learning itself can provision deeper discussion and enhance creative problem-solving. The team also wanted to develop a set of terminology that would suit the application to fully online asynchronous courses. Much of the language around learning is framed around the teacher. Laurillard (2002, 2012) introduces a set of learning types in her work around a Conversational Framework, a conversation that is participatory and between the teacher and the student. That scenario is quite different in the fully online space. Our reframing came from an idea to move from a teacher-centric model to one that was instructor-embedded, where the course itself became the method of instruction rather than an aside to it.

The changes we developed focussed on converting the types of learning to adjectives of learning and expanding some of the ideas and explanations to apply more broadly. For example, Collaboration is a specific type of interaction concerned with consensus and working together on a singular output. A term like Social Learning is more expansive and can encompass all forms of collaboration as well as cooperation and sharing, where they learn from each other through an exchange of ideas. Through this process, the team developed a set of seven Learning Types:

- Assimilative - Learning through presented information.

- Investigative - Learning by seeking information.

- Formative - Learning by trying.

- Discursive - Learning by engaging with other perspectives.

- Productive - Learning by creating artefacts.

- Evaluative - Learning through feedback.

- Social - Learning with others.

These types of learning provide a way to begin the key discussions in learning design. Working from a list of topics, it becomes possible to discuss several different ways of learning. Working collaboratively, we can use the Learning Types to construct learning sequences that take learners through different learning processes. Learning from information, then putting that into practice and receiving feedback. It creates an opportunity to explore pedagogies — the possibility of multimedia learning, dual encoding, recall and application of skills and knowledge.

The Learning Types were then mapped to seven Activity Types. The learning types help define the best ways for learners to engage with topics or concepts, whereas the activities help define the planned learning experience and outline what needs to be curated and created during course development.

- Assimilative = Content - Creating information for the student to learn from.

- Investigative = External Resources - Curating information for the student to engage with.

- Discursive = Discussion - Creating opportunities to share and engage with different perspectives.

- Formative = Practice - Providing opportunities for learners to try things out.

- Productive = Assessment - Students produce artefacts as evidence of learning.

- Evaluative = Review - Creating opportunities to learn from reflection and from feedback.

- Social = Interactive - Creating opportunities to learn from others.

Having this set of vocabulary enables conversations to occur, and the choice to keep the language simple and accessible ensures that it is relatable and understandable for academics to express their ideas and discuss the methods behind their own teaching practices.

Learning Patterns

Whilst the Learning and Activity types help define the overall learning experience, they become less useful as you get into the development of individual lessons and activities. What exactly can and does Content or Practice look like? A missing piece was required to aid the development of a sequence of learning so the idea of Learning Patterns was introduced. Based on the concept of a Pattern Language (Alexander, 1977), Learning Patterns are a reusable scaffold to aid the design of a learning experience. They provide a superstructure or way of thinking that can be reused and recombined to suit different contexts and topics. The Patterns developed (Klapdor, 2022) act like Lego, simple shapes that fit together to create unique student experiences. Their usefulness comes from the fact that sequences can be adapted to suit the lesson's purpose and scaffolding provided to help author that aspect of the course.

Knowledge Aspects

The knowledge aspect of learning design focuses not on the knowledge itself but on how it is structured and presented to learners. This part of the system focuses on the processes and ways of working with knowledge and being able to convert it into a learning experience. Rather than developing a templated process, the team set out to create one that was adaptive to the unique nature of each course – its concepts, topics, discipline and teacher.

Agile Learning Design

These principles were created to combine the bespoke nature of design with the context and content of the courses we work on and the broader need to scale up our production and capacity. What has come out of that effort are some distinct principles that guide how we work.

Rather than developing a templated process, the team set out to create one that was adaptive to the unique nature of each course – its concepts, topics, discipline, and instructor.

The principles that were developed sort to combine the bespoke nature of design that suits the context and content of the courses with the broader need to scale up our production and capacity. What has come out of that effort are some distinct principles that guide how we work.

- Understand the constraints. Set out the timeline for development, duration of the course, expected study time, desired outcomes and the required evidence of learning needed.

- Design with purpose. Seek out the moments of joy, wonder and understanding to specifically design opportunities for them to occur.

- Ask big questions for little details. Ask big questions of the course to define what the experience needs to be. How should it change learners? What will they remember in 5 years or 10 years about this course?

- Shape is emergent, the scope is set. What the course consists of will emerge from the process, don’t seek to define it too early. The scope of the course provides the constraints, and they will help guide decisions.

- Containers and fidelity. Content is a container word for ideas that over time are transformed. Begin with dot points, add paragraphs, add guiding comments and increase the fidelity over time.

- The key to success is to iterate. Snowball not waterfall. Move things around, don’t be afraid to change and adapt. The default might be always to add more to the course, it is just as important to remove and subtract to make things clearer for the student.

- Be water. The Learning Designer's roles and responsibilities need to adapt to the course, the discipline and the individuals they are working with.

These principles helped to define and develop the process we use for course development.

Milestones and Artefacts

During the scale-up process, meeting commercial deadlines was crucial. It was necessary to create, finalize, and approve courses within a strict time frame for teaching. This required a faster development process than the University was used to and the OPM provider faced challenges with faculties not accustomed to working under the deadlines of this linear development process. The OPT was frequently brought in to help negotiate and resolve problems as they arose, adding extra staff and effort to ensure successful completion.

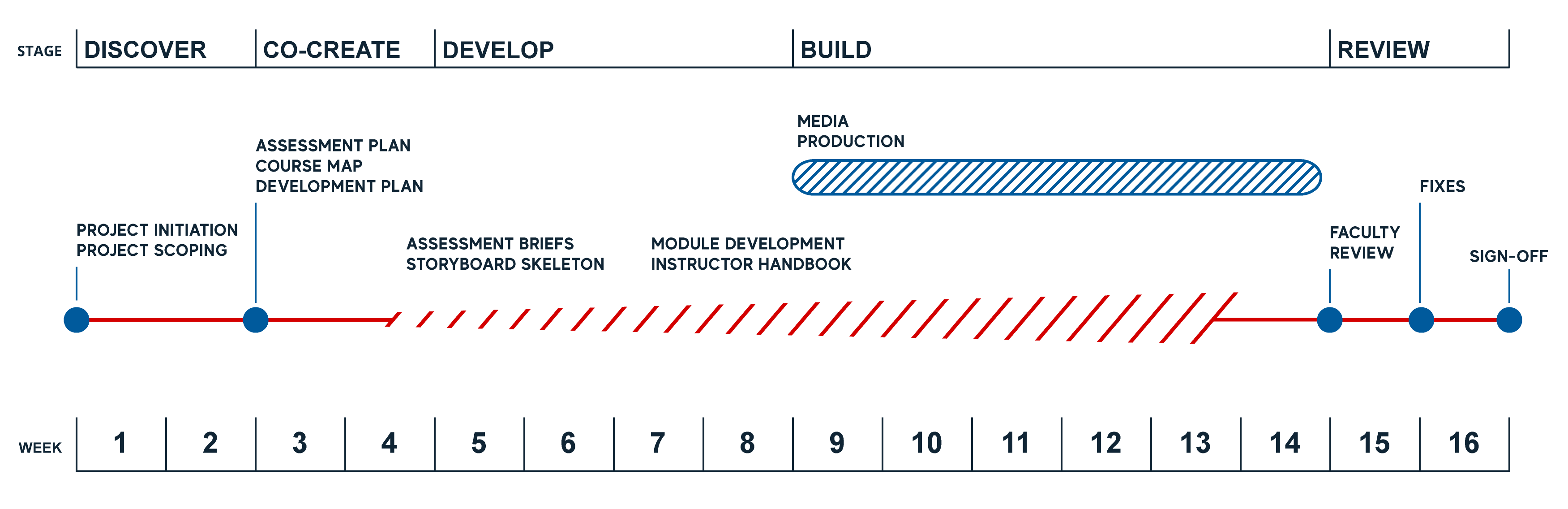

In contrast the OPT utilised a more agile and iterative approach during MOOC development which seemed more capable of adapting to challenging circumstances and issues as they arose. As the relationship developed with the OPM, a concerted effort was put into developing a more iterative approach to design and development that was more Snowball than Waterfall (Klapdor, 2021). Courses were mapped and planned, and then detail was added in cycles. This way of working required different project management processes, which were developed over the last four years, that is based on Milestones and Artefacts. The completion of milestones ensures that the project is on track to meet its deadline or that interventions are required, which are met through the production of specific course artefacts. These are discussed further and marked as bold in the Development Process.

Technology Aspects

The technology aspect started with the development of a Program Style Guide. This initial work took place during the development of the MathTrackX MOOCs where a range of conventions for designing content and styling it in the LMS were developed. The conventions weren't just content related; they also contained pedagogical information and provided visual context for the learner. For example, content placed into 'cue boxes' visually contains the information and provides students with a visual cue as to what that content is - this is important, this is a rule, this is an example. The other convention was around 'direction boxes', which contained information and instructions related to completing a task. These made pages much easier to navigate, find information on the page and, when required, perform an action. In time a full stylesheet with reusable elements was developed that is centrally managed and integrated into the main university LMS, initially for our projects but is now available to the whole institution.

The design phase has always been difficult to find technology suited to the task. While we originally used paper-based techniques, Covid restrictions meant that an alternative needed to be found. Miro met our needs for collaboration, we could create Templates for course workspaces and provide a guided and highly collaborative process of design and conceptualisation. We could also use features of Miro to generate key artefacts in the process - like mapping constructive alignment, developing a Course Map, a time-on-task table and colour-coding to communicate aspects of the learning experience.

The technology used during the development of a course was always problematic because nothing bespoke was ever available. All initial processes were built around wordprocessing documents that were troublesome. They lacked true collaboration features, and we were plagued with version control and sync issues. The unwieldy nature of documents played havoc across the teams and various programs we worked across and while it was possible to produce courses this was, it was rarely seamless and was always less efficient and required more labour and heartache than should be necessary. The team had started to formulate some ways of getting around some of these limitations and, through a collaborative effort, started to develop the Smart Storyboard in 2022.

The software breaks down the course into smaller components, Course > Modules > Lessons > Blocks and creates separate areas for developing Assessments, Discussions, Quizzes and Teaching Sessions. Each component can have its own metadata attached to it and has its own status and assignee, so work can be managed, allocated and tracked in real-time across academics, learning designers, learning resource developers, digital education developers, project officers and team managers. This allowed the team to develop a single course of truth to work on, manage, and report on the status and assignment of more granular aspects of the course. This has created huge efficiencies in reporting for the management of each development cycle, but also allows learning designers to visually appraise the course and adjust on the fly and as required. The key to the tool's functionality is the ability to break the course into Blocks, and each block has its own metadata attached and allows the use of Learning Patterns to help provide scaffolding for the lesson and guidance for each block in the course.

The Smart Storyboard also simplifies the development of the final course site and all the media in the course. It contains its own production workflow for media, allowing work to be spread across teams and worked on concurrently. When the course is ready, it allows for the direct export of structured HTML ready to be copied and styled using the UoA Style Guide into any LMS platform, simplifying the whole production process.

The Development Process

The Organisational, Pedagogical, Knowledge and Technological aspects all come together during the Course Development Process. The reality of course development is that it is a project with resources available within a set timeframe and an end date. Over time the team developed and refined a process to ensure that high-quality courses were developed and delivered on time using more agile techniques. The process is not in itself unique, but it is proven to scale across multiple programs of learning and simultaneous course development.

Figure 2: The Online Programs Team course development process.

- Discover - The Discover stage kicks off the process and provides time for the learning design team to understand the course and areas of development. The Course Catalogue artefact collects information about the current course, existing resources, student evaluations, lectures - whatever is useful in understanding the starting point of the course. The catalogue helps to develop a Course Report, a consolidated plan for developing the course.

- Co-create - The Co-create phase is where the whole-of-course design work takes place. This phase aims to set up the course's parameters and map out the structure over its duration. The first output is the Assessment Plan, which focuses on constructive alignment and frames assessment as evidence of learning, proving that the students can demonstrate the desired learning outcomes. The Course Map is a clear and concise map of the course across its duration, in our case, a 12-week trimester. Assessments are plotted out first, including a start and end date. The knowledge and skills required to complete the assessments are then used to map out the topics across the weeks. Topics are then turned into Lessons - addressable questions that have a clear purpose and intent. Rather than creating another set of learning outcomes for each week, we have found it much easier to break down a topic into What, How, Why, Who, When and Where questions. This form of lesson aids in communicating each week's goals and develops a shared understanding between academics and learning designers as to what needs to be achieved in the course. Once lessons are developed, the colour-coded Activity Types are used to create a visual of the planned learning experience. This helps diagnose a lack of different types of activity and learning throughout the course. This is expanded to map out the weekly student Time on Task across the course, which helps ensure that we have a consistent level of work across the trimester.

- Develop - The Develop stage is where the full course is created as a storyboard prior to being built in the Learning Management System (LMS). The Smart Storyboard provides a space for the bulk of the work to be done and allows for the various aspects to interact and come together. For example, one of the tool's functionalities is the ability to break the course into Blocks. Each block has its own metadata and allows us to assign a Learning Activity and a Learning Pattern to help provide scaffolding and guidance to develop that specific activity. The blocks allow a learning designer to work iteratively with an academic, sketching out learning sequences in a lesson as dot-points and using patterns that can be developed over time, using the tool to swap status and assignee as it is developed. This also allows for lessons to be developed in platform as they are ready, rather than waiting for the whole course to be finalised. It provides a tool for agile development that has previously been impossible.

- Build - The media production team handles the build stage and moves the content from the Smart Storyboard into the LMS. The cloud-based Smart Storyboard allows for the direct export of structured HTML ready to be copied and styled using the UoA Style Guide in the LMS platform. This allows for an LMS agnostic or multi-LMS approach to publishing. During this phase, the development team brings to life the course's planned visual, multimedia, interactive and video elements. The final artefact of this is the Course Blueprint – the master template for the course used for future rollouts and delivery. In most instances, Build takes place concurrently alongside the Develop stage as individual elements can be created.

- Review - The review stage has students and faculty complete a full review of the finished course in the LMS. The development team then fix any errors that are encountered and perform our own quality assurance processes before final signoff. These include checks on accessibility and a review of the course using our Course Assessment tool, a rubric based on how the course meets the Adelaide Online Learning Experience. Once the course development is complete, it is set up for teaching. A First Run Review of the course to review the experience of the live course and to conduct any tweaks to the course, particularly around assessments and activities. The review helps us to circle back around to the Learning Experience and is used to inform the next set of courses.

The system isn’t static, nor is it complete. The work pioneered by the team is now informing the mainstream development process across the university. A system that has been developed to improve the capacity and capability of the team is now increasing its scope across the institution and forming the backbone of Learning Design projects across the institution.

References

Alexander, Ishikawa, S., & Silverstein, M. (1977). A pattern language : towns, buildings, construction. Oxford University Press.

Fensel, D. (2001). Ontologies: Dynamic networks of formally represented meaning. Amsterdam: Vrije University.

Higher Education Standards Framework 2015 | Tertiary Education Quality and Standards Agency. https://www.legislation.gov.au/Details/F2015L01639 Accessed July 2023

Klapdor, T. (2021). The key to success is to iterate, Heart | Soul | Machine, retrieved from https://timklapdor.wordpress.com/2021/06/18/the-key-to-success-is-to-iterate/ July 2023

Klapdor, T. (2022) Learning Patterns Library, retrieved from https://learning-patterns.com/ July 2023

Laurillard, D. (2002). Rethinking university teaching: a conversational framework for the effective use of learning technologies (2nd ed.). London: RoutledgeFalmer.

Laurillard, D. (2012). Teaching as a design science: building pedagogical patterns for learning and technology. London: Routledge.

McDevitt, K. & Ricci, M. (2016). From practitioner-producers to knowledge cocreators: An early view of a design-based research project to foster insight generation into MOOCs. In S. Barker, S. Dawson, A. Pardo, & C. Colvin (Eds.), Show Me The Learning. Proceedings ASCILITE 2016 Adelaide (pp. 392-396).

Standards from the Quality Matters Higher Education Rubric, 7h Edition. Quality Matters. Retrieved from https://www.qualitymatters.org/sites/default/files/PDFs/StandardsfromtheQMHigherEducationRubric.pdf July 2023

TELAS Accreditation Framework (2020). Published on the TELAS website, retrieved from https://www.telas.edu.au/framework/ July 2023